#25 and Sisyphus

Thoughts on Burden

I’ve read variations of the story, but the story always ends up the same: he must push a stone up the hill and watch it fall to the bottom forever.

Studying literature, the story of Sisyphus was regarded with a certain reverence. Talking about it in class or among my peers, it felt like we ought to whisper this story around our group. It is something too true to actually speak and would perhaps be a story better titled “Untitled (The Myth of Sisyphus)” so as to not be too direct with the obvious truth, and that is: should I ask if life is meaningless?

I remember a grad seminar where the professor took advantage of the pause mentioning Sisyphus sometimes brings and asked “For whom is this hell?”

This is the right question. Without doubt, the issue that many take with the myth of Sisyphus is that it seems to be the ultimate loop of meaninglessness and struggle. This myth draws too much attention to the sentiment of burden, a state of deep pressure in a task that is without payoff or end. All action and effort are neutralized by futility under this burden. One is lost to the monotony of wondering why the stone needs to be rolled at all. This myth is hell for those who need progress.

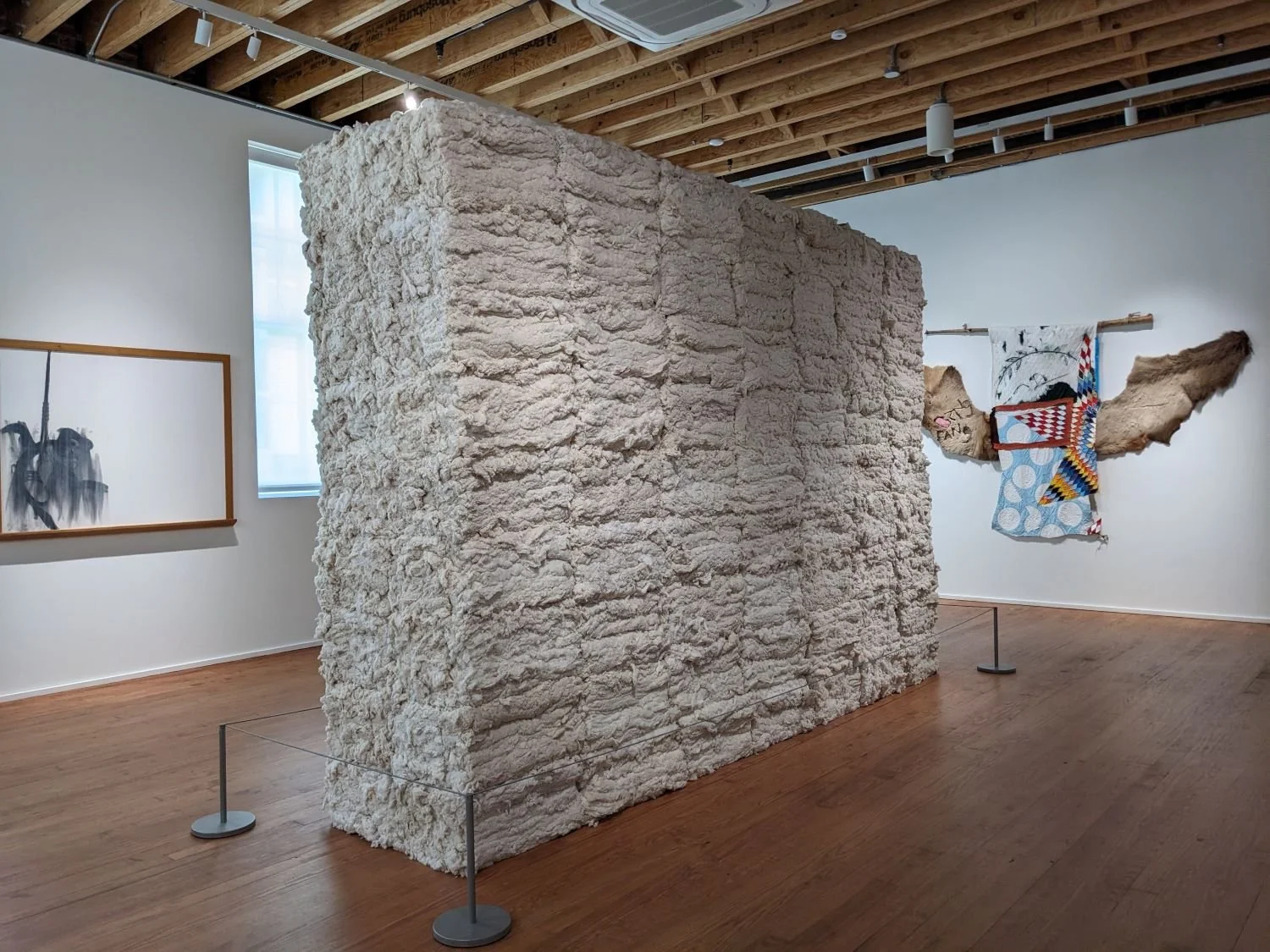

I couldn’t help but think of this while I stood in front of Leonardo Drew’s “Untitled #25” at the Rubell Museum.

This work is mammoth in nature, and the plaque shows two pictures of him rolling these massive bales of cotton down Broadstreet. It calls to mind the tremendous feat completed and re-lived endlessly by Sisyphus. The massive carrying and pushing of things only to find the bail has arrived at the start of the hill again.

The project Drew works on here would appear to be finite. It seems there simply is an amount of cotton that is eventually all transferred from one place to the next for his work. It would be safer if Drew’s work did not fully mimic the myth, but the name of the piece tells me it is not the case. The name of the pieces tells me that it is only the 25th iteration. There is no better way to demonstrate routine that explicitly calling out which attempt this round is. Naming the piece “#25” communicates there have been others before and there will be others after.

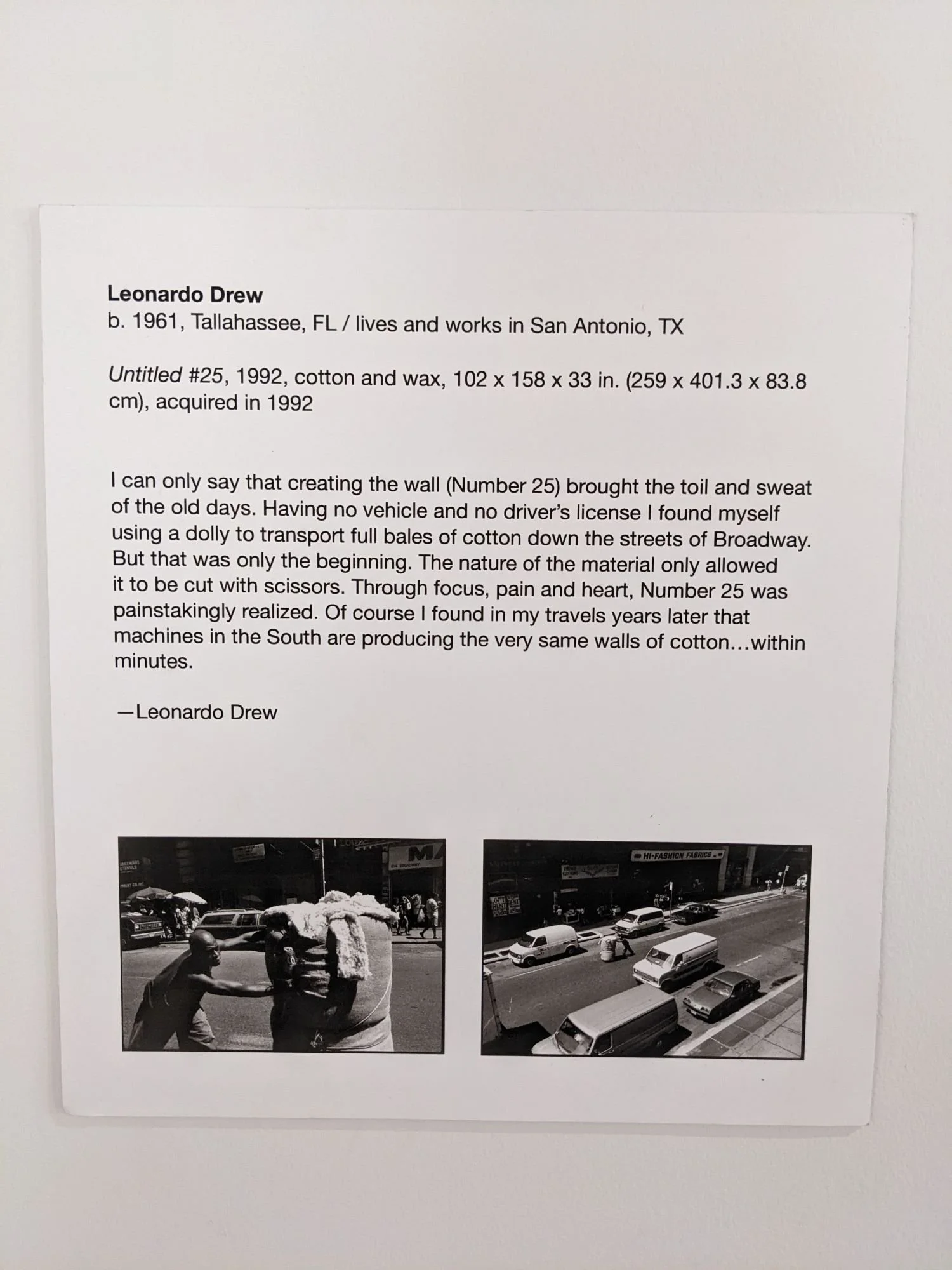

Specifically, it is the didactic description with a quote from him that made the full picture arrive.

The moment arrives when at the end of the quote he discovers that machines can produce the same output in a matter of minutes.

This is the moment that takes this from project to art. The work is the project that requires the labor of time and sweat, but it is absurdly undone when noted that this could have all been avoided with the use of machines. This is curation at its finest. Without including the quote of him wondering about how machines could do this work anyway, it is simply a statement. But, instead, it points to the true absurdity of, in fact, soul-crushing labor. As he states, it “brought the toil and sweat of the old days.”

It would be immature to avoid how this is a commentary on slavery. As I shared before from earlier reading, the transatlantic slave trade was an economic decision. In the same way that machines could (and will replace) the work of today, so too could they have replaced slave labor, if somehow possible. His commentary seems to be a dismayed leer.

The work of the art does not “occur” until the moment when he then, crucially, realized and stated that the work wasn’t necessary. It didn’t need to happen.

More soon,

Trevor

Now-reading affiliate links: